Revealing Manheim’s colorful past

History of Manheim and “Baron” Henry William Stiegel

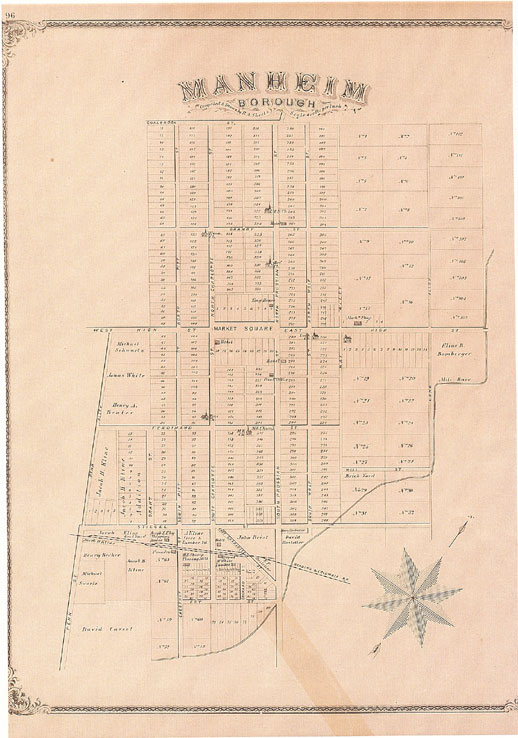

Officially founded in 1762, the town of Manheim rightfully belongs on a select list of Pennsylvania towns that precede the Revolutionary War. The land on which the town was laid out shared a close connection to the family of the Pennsylvania colony’s founder, William Penn. It was in 1734 that this bountiful tract of acreage in Donegal Township was gifted to Penn’s faithful secretary, James Logan, by his widow and sons. Eventually, in 1762, this same land (purchased from Logan’s granddaughter) would attract the attention of three Philadelphia businessmen: Henry William Stiegel and his associates, Charles and Alexander Stedman. Stiegel and the Stedman brothers must all properly be considered as the founders of the town of Manheim, although Stiegel is the only one of the trio who left any lasting impression. For years, the story of Manheim – or Stiegeltown as it was known among many farmers – could not be told without including the accomplishments and career of this remarkable man.

Traveling from Cologne, Germany with his widowed mother and brother Anthony, Henry W. Stiegel arrived in Pennsylvania in 1750. He found his first employment in the busy wharves of Philadelphia as a clerk with the Stedmans, prominent English ship faring merchants and port agents who years before had escaped persecution in Scotland after a failed attempt to support a retaking of the Crown. During this two years of employment with the Stedmans, he became associated with an ironmaster in Northern Lancaster County by the name of Jacob Huber of Elizabeth Furnace. Beginning once more as a clerk, he rapidly progressed his favor and fortune while also attending to his mother and brother in the nearby village of Heidelberg (Schaefferstown, Pennsylvania). After a few short years of employment and a marriage to the ironmaster’s daughter, Stiegel became part owner of the furnace along with his partners, the Stedmans, after Huber’s resignation of ownership. The ironmaster’s daughter, Elizabeth Huber, would have two daughters, Elizabeth and Barbara, however her untimely death would lead Stiegel to take a second wife, Elizabeth Holtz of Philadelphia, to whom a son Jacob was born. Under the craft and guidance of Stiegel, the furnace was expanded with the purchase of Charming Forge near Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania.

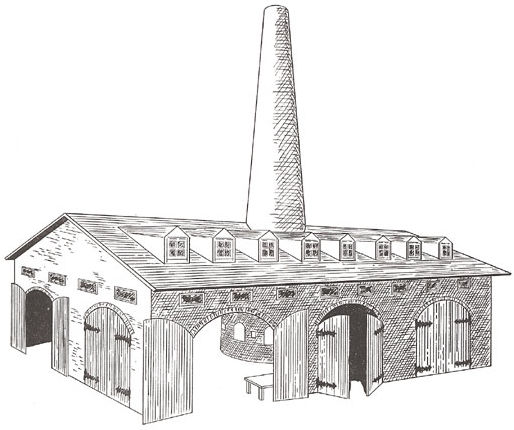

Stiegel prospered as an ironmaster while simultaneously becoming prominent in church and civic affairs, and soon realized he had more to offer than his iron and forging skills. The 160 square miles of land redistricted in 1741 from within Dongeal Township to create Rapho Township would prove to be Stiegel’s garden spot, fine tuning his visions to the predominantly German compatriots living around him. It was in 1762, with help once more from the Stedman brothers, that the town of Manheim was planned, including with it the entities of Stiegel’s industries. With his newly forged success in experiments in glass making, leading to the manufacture of window glass and bottles at Elizabeth Furnace, there can be no doubt that while many settlers before him sought religious and agricultural liberties, Stiegel had a clear and definitive plan of making Manheim the seat of an industrial empire.

A Town is Born

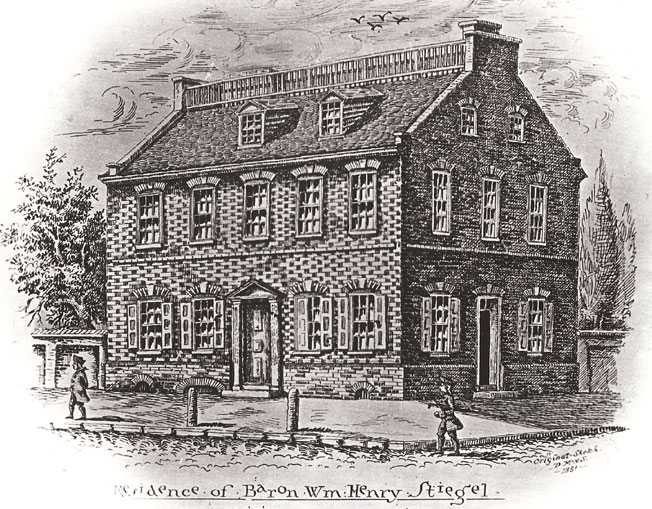

The layout for Manheim provided a wide open space in the center of town now known as Market Square. In the square, Stiegel called for an imposing mansion and an office building to be erected, while a few blocks south on the corners of Stiegel and Charlotte Street he directed the construction of a manufacturing plant to continue the glassmaking begun at Elizabeth Furnace. Called a “glasshouse” by Stiegel, the first glass was blown there in late 1764 and continued into the forthcoming years of the Revolution. Throughout this period, the glasshouse would expand several times, attracting skilled craftsmen from glassmaking foundries across Europe and eventually earning the title of the American Flint Glass Manufactory. His workforce, intrigued by extensive newspaper advertising, contributed to the quality and variety of table and chemical ware produced at the works which brought increased patronage from the cities of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, as well as from nearby towns like Lancaster. Stiegel’s hard determination for recognition in the glass world paid off, and in time he had the satisfaction of hearing authorities adjudge his glass equal to that imported from Europe.

Stiegel carried on the operation of the Manheim glassworks which eventually was given the name of the American Flint Glass Manufactory. He enlarged the plant several times and hired skilled workmen from the European glassmaking centers, which contributed materially to the quality and variety of tableware, as well as chemical ware, manufactured at the works. Extensive newspaper advertising brought increased patronage from the cities of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, as well as from nearby towns in Pennsylvania. Stiegel had to literally fight for recognition and in time had the satisfaction of hearing authorities adjudge his glass equal to that imported from Europe. He had truly become as eminently successful in glassmaking as he was already prominent in the iron industry. Henry William Stiegel led a rather colorful and somewhat eccentric life. We are certain he lived on a scale far more elaborate than that of his neighbors. For this reason Stiegel was dubbed “Baron” and the title has persisted, and even to this day he is spoken of and written of, as Baron Von Stiegel.

The legacy that Henry William Stiegel left behind reveals him as a man of other interests apart from his career as an ironmaster and glassmaker. Being the progressive man that he was, Stiegel saw the need for education and as his fortune grew, had schools built and hired schoolmasters to educate the children of his workers. Also an accomplished musician, he supported a band in Manheim and directed the choir of Trinity Lutheran Church (Lancaster, PA) at dedication services in 1766. Deeply concerned with affairs of the church, he gave his fellow Lutherans in Manheim a lot of ground on which to build a church “for five shillings and in the month of June yearly hereafter the rent of One Red Rose if the same shall be lawfully demanded”. From this sentimental stipulation – though seldom recognized over the following 120 years – bloomed the Festival of the Red Rose in 1892, an event still annually observed to this day by Zion Lutheran Church on the second Sunday in June, when a red rose is paid in legal manner to a descendant of Henry William Stiegel.

Continuing his proprietary interest in Manheim, he gradually became sole owner of the town through a series of complicated financial transactions involving the Stedman brothers and other wealthy Philadelphia colonists. Shortly thereafter, Stiegel along with the rest of the colonies suffered financially as the relationship with England began to sour. In the years immediately preceding the war, Stiegel’s finances collapsed, leaving him with debts and reverses to his lenders and investors, and even necessitating a brief incarceration in debtor’s prison. It was some time in 1775 that production ceased at the glassworks and Stiegel left Manheim without title to a square foot of land in his town. Through the charity of a kindly creditor, he would briefly take residence again at Elizabeth Furnace, though this property and Charming Forge would ultimately passed out of his possession. Completing his ruin, Stiegel found himself dependent on relatives, at times teaching school or finding employment at various iron furnaces.

The Revolutionary War

In 1777-78, as the colonies dug in deep for war with England, the house which Stiegel built on the Square in Manheim functioned as the family home of Revolutionary patriot and financier Robert Morris. Consequently, as the Continental Congress met in York, Pennsylvania during British occupation of Philadelphia, also living in the town were the families of Dr. Joseph Shippen, Surgeon of the Continental Army, and Colonial Post-master General Richard Bache, whose wife was Benjamin Franklin’s daughter. In 1778, while a military hospital was maintained in the Reformed Church on North Prussian Street (now Main Street), Dr. Andrew Craigie, Apothecary-General of the Army, urged the “proprietary of setting the glass works at Manheim agoing” as the Continental Army Medical Department was “destitute” of bottles.

Regrettably for Dr. Craigie and Manheim, the glass factory which Stiegel had augured and established so well for the future of Manheim was never operated with any success after the failure of its founder. Over the years of the war, several feeble efforts to rekindle the furnace were made with little to no success, and the fires were put out for good around 1780. This left Manheim a struggling village of barely 300 people, although the publication of the first Federal Census in 1790 dignified its residents with the Manheim town name. Like the rest of the newly established United States, growth was slow and progress plateaued. The first sixty years of Manheim’s history would be enough to once again establish recognition, however, as by 1838, with a population that had only reached 365, the town was incorporated as a borough by the State Legislature.

For nearly fifteen years, Henry William Stiegel’s professions of iron and glass would make him one of the most outstanding industrialists of colonial Pennsylvania. He had become as eminently successful in glassmaking as he was already prominent in the iron industry, allowing him and his family to lead a rather colorful and somewhat eccentric life in the colonies up until his financial ruin. For this reason, time and story have told of his far more elaborate lifestyle than that of his neighbors, sounding the cannon from high on his hill top tower home to and from his journeys, earning him the pseudo title of “Baron” von Stiegel, a name which holds in both spoken and written biographies to this day.